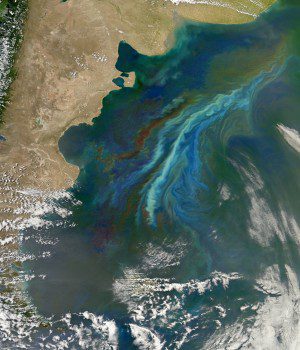

Satellites use chlorophyll's green color to detect biological activity in the oceans. The lighter-green swirls are a massive December 2010 plankton bloom following ocean currents off Patagonia, at the southern tip of South America. (Credit: NASA's Earth Observatory)

New research using NASA satellite data and ocean biology models suggests tiny organisms in vast stretches of the Southern Ocean play a significant role in generating brighter clouds overhead. Brighter clouds reflect more sunlight back into space, affecting the amount of solar energy that reaches Earth's surface, which in turn has implications for global climate. The results were published July 17, 2015, in the journal Science Advances.

The study shows that plankton, the tiny drifting organisms in the sea, produce airborne gases and organic matter to seed cloud droplets, which lead to brighter clouds that reflect more sunlight.

The clouds over the Southern Ocean reflect significantly more sunlight in the summertime than they would without these huge plankton blooms, said co-lead author Daniel McCoy, a University of Washington doctoral student in atmospheric sciences. In the summer, we get about double the concentration of cloud droplets as we would if it were a biologically dead ocean.

Although remote, the oceans in the study area between 35 and 55 degrees south is an important region for Earth's climate. Results of the study show that averaged over a year, the increased brightness reflects about 4 watts of solar energy per square meter.

McCoy and co-author Daniel Grosvenor, now at the University of Leeds, began this research in 2014 looking at NASA satellite data for clouds over the parts of the Southern Ocean that are not covered in sea ice and have year-round satellite data. The space agency launched the first Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) instrument onboard the Terra satellite in 1999 to measure the cloud droplet size for all Earth's skies. A second MODIS instrument was launched onboard the Aqua satellite in 2002.

Read the paper at Science Advances: advances.sciencemag.org/content/1/6/e1500157