GEOINT of the people, by the people, for the people offers big benefits for the geospatial intelligence community.

By Luke Barrington, senior manager, DigitalGlobe (www.digitalglobe.com), Longmont, Colo.

Using new forms of data, including satellite images, photo-sharing and social media, the crowd has become an indispensable producer of GEOINT data.

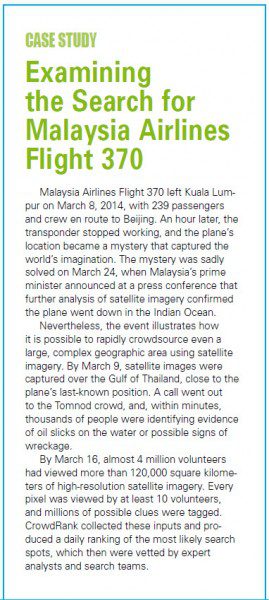

How many vehicles, fighters and refugees are involved in the conflict in South Sudan? What is the extent of damage to buildings and agriculture production caused by the revolution in Syria? Where should the U.S. Navy focus its search for Malaysian Airlines Flight 370? These questions highlight tasks that geospatial intelligence (GEOINT) professionals address every day: mapping buildings and infrastructure; identifying vehicles, people or objects; and searching for needles in a global haystack.

Extracting GEOINT at a planetary scale is an enormous challenge. For example, the Arab Spring in 2010 inspired protests in Syria in early 2011 that spilled over into revolution by 2012 and is now a full-blown civil war. Tracking the evolution of these events, mapping them across an entire nation and understanding the real-time consequences are daunting tasks for a single analyst.

However, with global challenges comes a global solution. Connected online, the international community now rallies around challenges like reporting damage, counting vehicles, tracking events and mapping war zones. Using new forms of data, including satellite images, photo-sharing and social media, the crowd has become an indispensable producer of GEOINT data. However, as with any new form of data, gathering, understanding and assessing the reliability of crowdsourced information is a new frontier for GEOINT analysts.

Pairing Satellites and Eyeballs

Satellites collect millions of square kilometers of Earth imagery every day, gathering amazing data about our planet. This relentless influx of pixels contains valuable information about important locations, objects and events across the globe. Potentially, every home and office, car and plane, flood and fire may be captured, recorded and extracted using satellite imagery.

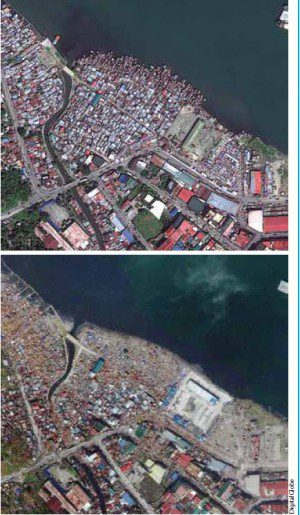

One of the areas most damaged by Typhoon Haiyan was identified by crowdsourcing near Tacloban, a city of about 250,000 people.

Although the GEOINT community has made incredible advances in the use of increasingly sophisticated algorithms to analyze imagery, nothing to date matches the perception and intuition of the human brain. Humans excel at identifying locations that look interesting, objects that are new or events that seem important. Such complex cognitive tasks, while simple for us, are difficult to automate with

machine algorithms. Exploiting human analysis at the volume and velocity of any imaging satellite constellation is a huge task. Much of the valuable insight locked inside these pixels is never realized simply because of the overwhelming challenge of looking at them all.

So how can we extract rapid, reliable, human insight from trillions of pixels? By scaling the data analysis challenge across a massive human network, working in synchrony, we can expand our understanding of what imagery tells us about the world. The idea that many hands make light work is the essence of crowdsourcing. Large, interconnected groups of humans, working in a coordinated effort on a shared goal, can uncover insights and accomplish feats that would be impossible for a single individual.

How Crowdsourcing Works

The ideal is achieved by combining the efficiencies of technology with the intelligence of human analysis. DigitalGlobe (www.digitalglobe.com) achieves this ideal with Tomnod, an online crowdsourcing network of thousands of volunteers who contribute to satellite imagery analysis.

Anyone who has used a smartphone to map a commute or look up a house on Google Earth is familiar with basic GEOINT and satellite imagery interpretation. An intuitive Web interface builds on this widespread familiarity and empowers almost anyone to contribute to imagery analysis campaigns.

Crowdsourcing satellite imagery after the devastating May 2013 tornado that struck Moore, Okla., pinpointed every destroyed home (orange) and damaged roof (blue).

Tomnod divides massive image datasets into many small tiles and sends each tile to multiple individual users. Each member of the crowd is asked to identify relevant features in the tile”maybe locating homes damaged by a tornado, pinpointing cars in a parking lot or mapping religious sites in a city.

It's impossible to guarantee that every individual in the crowd has the experience, expertise and energy to identify all the complex or subtle features in a satellite image. But crowdsourcing works by identifying consensus among multiple, independent people, each working on the same image.

As users examine each pixel from each image tile and provide their interpretation of the imagery, the wisdom of the crowd begins to emerge. Each member of the crowd works in isolation, but when multiple individuals agree about a particular location or feature, analysts can be confident that something relevant has been detected.

As users examine each pixel from each image tile and provide their interpretation of the imagery, the wisdom of the crowd begins to emerge. Each member of the crowd works in isolation, but when multiple individuals agree about a particular location or feature, analysts can be confident that something relevant has been detected.

To date, the Tomnod crowd has been deployed on hundreds of satellite imagery exploitation campaigns, including:

¢ Situational awareness for humanitarian assistance and disaster response (see Typhoon Haiyan images above),

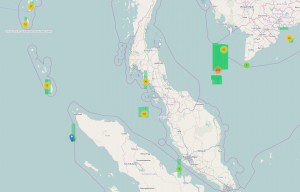

¢ Search and rescue support for missing people, planes and ships (see Examining the Search for Malaysia Airlines Flight 370 at right and the image below),

¢ Building damage detection for post-disaster insurance and reinsurance assessment,

¢ Vehicle and human activity detection for defense and homeland security,

¢ Wide-area surveying for oil and gas exploration, and

¢ Mapping and monitoring crucial supply chain infrastructure.

CrowdRank is a geospatial consensus algorithm that quantifies the degree of confidence in crowdsourced information. The algorithm works by calculating the agreement among all the individual contributors in the crowd. Every click from every user on the Tomnod website is analyzed by CrowdRank to compute two scores:

¢ The confidence in each location based on consensus among the crowd.

¢ The reliability of each individual based on his or her agreement with the rest of the crowd.

The search area for Malaysia Airlines Flight 370 covered more than 120,000 square kilometers. Areas in green highlight collected satellite images. Circles indicate the top locations of thousands of crowdsourced detections.

By assessing confidence and reliability of the crowd's contributions, CrowdRank takes hundreds of thousands of unverified inputs and transforms them into qualified, consensus detection. The result is a ranked list of important locations that decision makers, field responders or expert analysts can exploit to understand the information contained in the pixels. Crowd-Rank insight is delivered or integrated into existing GEOINT workflows via shapefile, KML, GeoJSON API, Web feature service, spreadsheets or custom analytic reports.

Assessing the Four Vs of Big Data

Big data problems often can be characterized by four challenges: volume, velocity, variety and veracity. Crowdsourcing can meet each of these challenges.

Volume

Crowdsourcing mobilizes a team of hundreds, thousands or even millions of volunteers who can cover vast areas of imagery many times over. Using crowdsourcing as a first pass over the imagery provides expert analysts and response teams with the clues they need to hone in on the most important regions.

Velocity

Exploiting satellite imagery with human analysts is an expert process that takes time. By applying hundreds or thousands of people to the problem, crowdsourcing increases the scale and speed of analysis immensely yet retains the accuracy of human insight. Analyzing 250,000 square kilometers of imagery might take weeks for a single analyst, but the task can be completed in a day using crowdsourcing.

Variety

A machine algorithm can learn to recognize cars, but it will fail to detect planes, ships or any of the infinite variety of other interesting objects on Earth. Crowdsourcing is flexible, matching the needs of the analysis by tasking the crowd to identify a variety of features such as buildings, infrastructure, objects and natural or man-made events.

Veracity

Everyone makes mistakes. But when consensus emerges among tens or hundreds of individuals, all pinpointing the same imagery feature, analysts extract true insight from crowdsourcing. Crowdsourcing gathers input from a crowd of independent humans and identifies the locations of maximum agreement. An algorithm such as CrowdRank computes the reliability of each person in the crowd and statistically determines the most relevant locations.

Join the Crowd!

The phenomenal response to Tomnod crowdsourcing campaigns has engaged a new kind of analysis in which millions of volunteers use high-resolution imagery to search vast areas with incredible precision. Moreover, crowdsourcing illustrates a new direction for GEOINT that uses individuals as data producers and consumers. Experts and novices work side by side, and human insight is augmented by automation.

Crowdsource satellite images yourself by visiting www.tomnod.com. You can view results from previous crowdsourcing campaigns and, with more pixels pouring in all the time, contribute to understanding new images of our ever-changing planet.