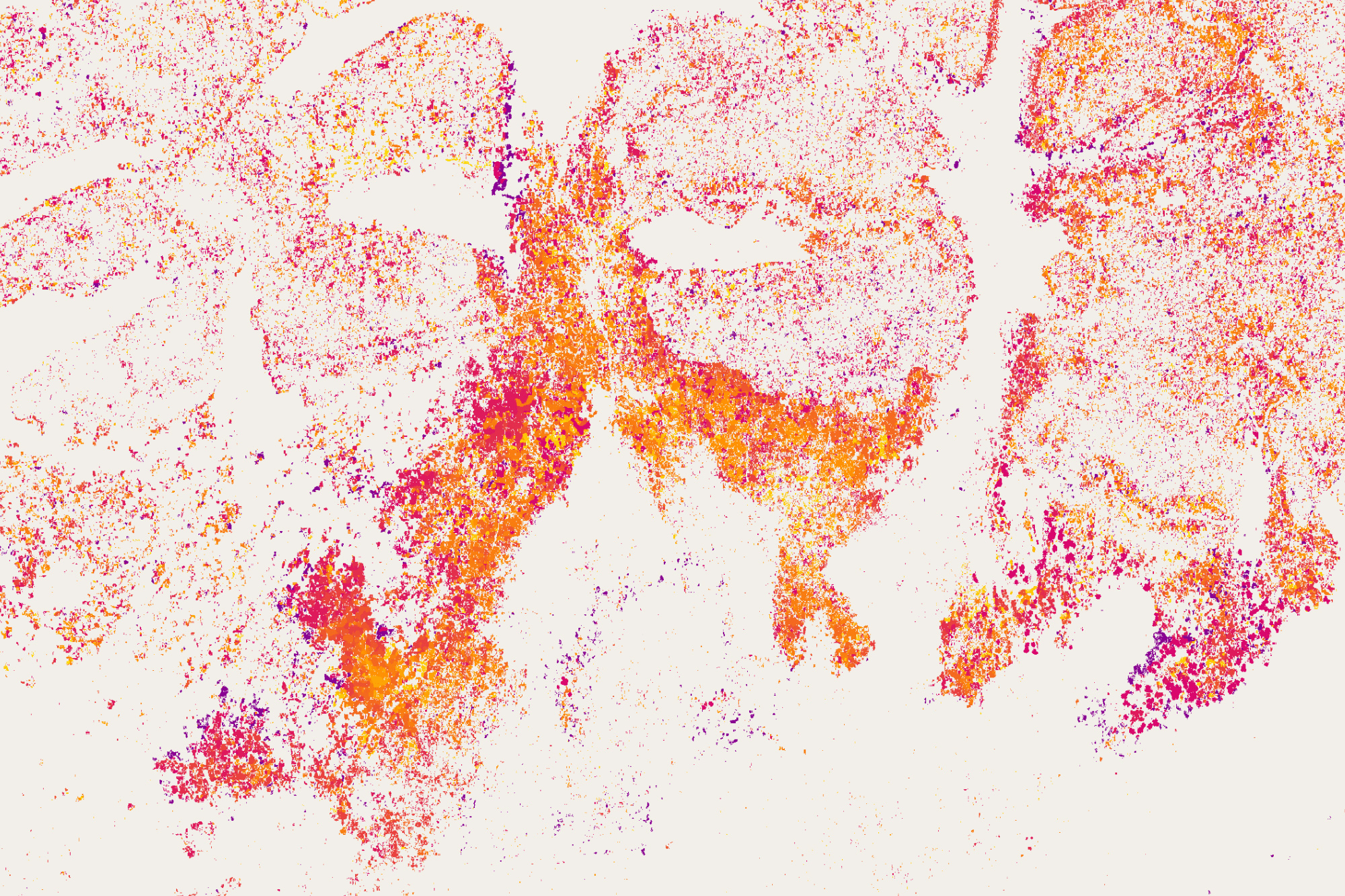

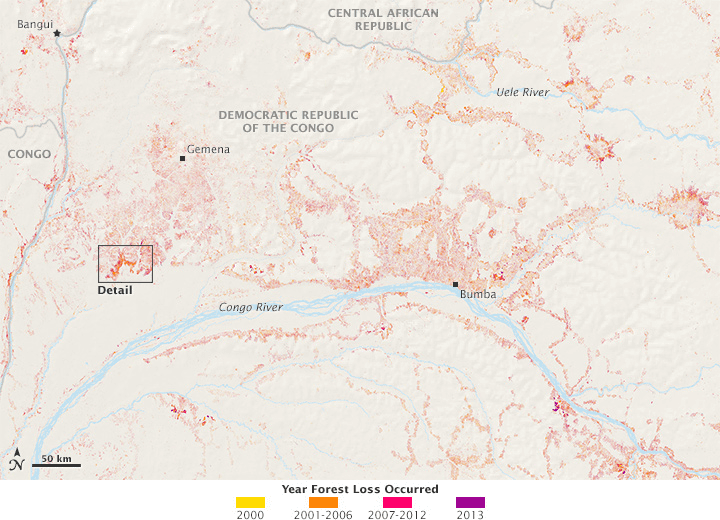

The accompanying maps show forest changes near the Congo River in central Africa as observed by Landsat between 2000 and 2013. Different colors represent the years in which forest parcels changed. Most of the forest losses were due to cut-and-burn agriculture where small plots of land were cleared for subsistence farming or for the use of wood for fuel. (Credit

NASA Earth Observatory maps by Joshua Stevens, using global forest change data from Hansen et al/University of Maryland.)

With at least one image of every location on Earth per season for 43 years, the Landsat data archive contains more than 50 trillion pixels. So how could you put all of that imagery to use in discovering and monitoring subtle changes on Earth? One answer lies in the clouds”cloud computing, that is.

Since the 1990s, University of Maryland geographers and remote sensing specialists Matthew Hansen and Sam Goward have been mapping changes in Earth's land cover. For years, they worked with low-resolution data, but disturbance happens on a small scale that demands something like the 30-meter resolution of Landsat satellites. The trouble was, researchers had to pay for every Landsat scene, and it was simply too cost-prohibitive to consider a global map. We did the science we could afford, Goward said, not the science we wanted to do.

Then in 2008, the game changed. Landsat data became free on the World Wide Web. We then knew we could make a global map, said Hansen, but we didn't have the computing power yet.

While attending an international meeting about deforestation and forest disturbance, he was introduced to Rebecca Moore, a computer scientist and mapping researcher at Google. Hansen saw an opportunity.

Their computing expertise fit perfectly with our geographic knowledge, said Hansen. So we ported our code for mapping forests to the Google system.

In just a few days, Google applied the University of Maryland analysis code to 700,000 Landsat scenes, discarding cloudy pixels and keeping clear pixels. They reviewed the remaining sequence of pixels and assigned a flag to each”was it forested or not? The analysis noted the date that forests were cleared or the date when they had grown-in enough to be counted as forest again. The entire process took 1 million hours on 10,000 central processing units. According to Moore, the analysis would have taken 15 years on a single computer. Above is a small sample of that forest-mapping effort.

Developing countries typically don't have current national forest inventories, if they have any at all. Maps like the Hansen-led effort provide a global standard for mapping as well as fill a void for nations and institutions. Armed with their data-rich maps, Hansen and colleagues would like to someday create a global forest loss alert system. The team is also working to develop tools to distinguish the causes of forest change”such as fire, mechanical removal, disease, storms”from afar.