The U.S. Geological Survey's recent success using drones to observe sandhill cranes in southern Colorado foreshadows the future of using unmanned aircraft for scientific research.

By Mike Hutt, U.S. Geological Survey, Rocky Mountain Geographic Science Center (http://rmgsc.cr.usgs.gov), Denver.

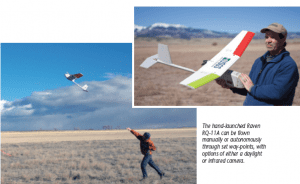

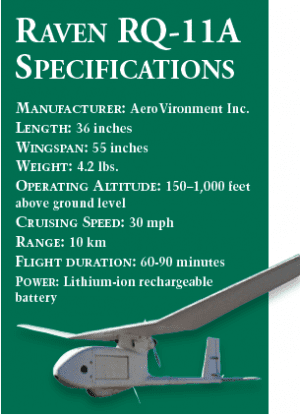

he Department of the Interior (DOI) recently conducted the first small unmanned aerial system (UAS) mission using the Raven RQ-11A UAS from AeroVironment (www.avinc.com) at Monte Vista National Wildlife Refuge near Monte Vista, Colo. The U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) Unmanned Aircraft Systems Project Office and Fort Collins Science Center collaborated with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) to determine the feasibility of using a UAS to capture videography of roosting sandhill cranes for estimating population abundance. The mission was the first UAS operation conducted by the DOI in the National Airspace System (NAS) using the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) Certificate of Authorization (COA) process.

Sandhill cranes are migratory birds that travel from nesting areas as far away as northern Canada and western Siberia in Russia to wintering areas in central and southern Mexico. The Monte Vista Wildlife Refuge is a primary migration stopover for the Rocky Mountain population of sandhill cranes during fall and spring migrations. Because the cranes congregate in relatively small areas on the refuge during the night, there's a high likelihood of obtaining accurate counts of the population. Traditionally, sandhill crane population surveys have been conducted during the day using fixed-wing aircraft. However, because cranes spread out across the landscape during the day to feed, these traditional methods are costly, time-consuming, and involve some level of risk for pilots and their crew.

Objectives and Operational Findings

Objectives and Operational Findings

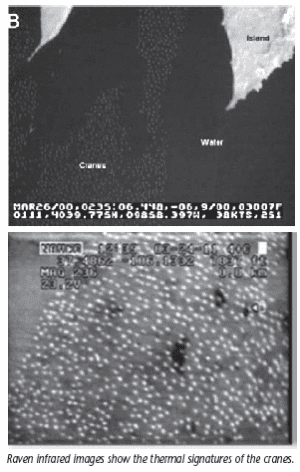

The objective of this proof-of-concept operation was to determine if the Raven's sensor package could detect the cranes' thermal signatures. Investigators also wanted to determine the cranes' behavioral response to the Raven while flying above them. Eagles are a predator of cranes, and biologists were concerned the cranes would view the UAS as a threat and react by flushing into the air when approached by the aircraft.

The reactions of the cranes to the UAS varied greatly by the time of day and the activity in which the birds were engaged (i.e., roosting, feeding or loafing). Sandhill cranes tended to flush at daytime feeding sites when the Raven approached, but observers noted no reactions during the morning civil twilight flights when the roosting cranes were settled. The results at loafing sites varied depending on the altitude of the UAS.

Video data from the early morning flights indicated the birds could be detected using a thermal camera sensor. However, because the birds began to fly at sunrise, the potential for a UAS/crane strike increased as morning progressed. Based on these results, and knowing that cranes typically don't fly at night, operators and scientists believe night flights over roosts would be the best procedure for capturing the videography. The birds are the most concentrated at that time, and the risk of a crane strike with a UAS would be low. Further, flying the missions at night would also reduce impacts to refuge operations and decrease the potential for incidents with the public.

After it was determined the UAS could identify the thermal signatures of the cranes, efforts were focused on collecting videography along several linear transects that then could be used to estimate the number of birds within a sampled site. Eight transect passes were completed over a chosen roosting site at 200 feet above ground level (AGL), as well as three collects at 300 feet AGL.

Accomplishing these collects under the current COA proved to be a challenge. The UAS operators had only a 25-minute window to fly the transects, because the cranes typically leave roosting areas at sunrise to feed in nearby fields. Once the cranes begin to fly, the risk of a mid-air collision increases and the ability to capture them on the imagery disappears. Because of the FAA restrictions in the COA, no flights could be conducted before morning civil twilight. Case studies for night flight approvals are being explored for future surveys. The USFWS land managers and biologists and USGS UAS operators believe night flight operations could be conducted safely while expanding the survey time of the collects.

Post Processing

With the videography collected, USGS analysts then converted the analog data into a digital format. The videos were reviewed and exported into still images. Analysts used the mosaics of these images to estimate crane abundance using a combination of methods, including manual extraction, automated segmentation and feature extraction. The estimate obtained using videography from the Raven UAS was compared to ground counts conducted by biologists from the USFWS Division of Migratory Bird Management. The count extracted from the Raven UAS videography (2,567) was close to that of the USFWS crew (2,692), a difference of only 4.6 percent.

Many milestones were reached during the project, notably the first approved UAS flight in the NAS for the DOI and demonstration of the importance of adapting the RQ-11A UAS platform. Although designed for military operations, the project demonstrated the key role the Raven UAS can play in collecting scientific data for improved wildlife management.