The Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks on America's home soil immediately prioritized homeland and national security to a level unparalleled in U.S. history. The critical need for qualified geospatial intelligence (GEOINT) professionals is on the rise, with far-ranging opportunities that include careers as geographers, imagery analysts, software technicians, database managers, application developers, engineers and remote sensing specialists.

Currently, seven U.S. universities offer Geospatial Intelligence certificates accredited by the U.S. Geospatial Intelligence Foundation (USGIF): George Mason University, The University of Missouri-Columbia, The University of Texas at Dallas, The University of Utah, The Pennsylvania State University (Penn State World Campus), the U.S. Military Academy (West Point) and the U.S. Air Force Academy.

The following articles were written by faculty members at some of these USGIF-accredited universities, illustrating the quality of educational leadership that a prospective student can anticipate from participating in such programs. For information about USGIF accreditation, visit usgif.org/education/accreditation.

Understanding the Geography of Terrorism

A broad-based geographic perspective on what motivates terrorists is indispensable to countering terrorism in the 21st century.

By George F. Hepner, Department of Geography, The University of Utah (http://geog.utah.edu), Salt Lake City, and Richard M. Medina, Department of Geography and Geoinformation Science, George Mason University (http://ggs.gmu.edu), Fairfax, Va.

Much of the research and scholarship on terrorism has focused on the vitally important perspectives of historical record, political organization, and social psychology of terrorists and their support groups. All such perspectives contain implicit recognition and use of geographic theories, concepts and analytical tools.

Terrorist literature, experts and derivative policy makers traditionally have focused on several geographic concepts as the underpinnings for their political or social explanations of terrorist group beliefs and actions. Such concepts include region, relative location, distance decay, core-periphery, insurgent state, geographic diffusion of ideas, technology and people, maps and imagery visualization, and sense of place cultural identity. In many cases, however, these geographic ideas and tools are used improperly.

Additionally, these ideas aren't explicitly described or recognized as the primary constituents and vehicles for explaining and understanding terrorist motivations and tactics. The roles of geographic practices and geospatial intelligence (GEOINT) aren't confined simply to geospatial technology. They require the integration of theory, methodology and techniques drawn from the breadth of geography to effectively address the issues of international terrorism.

Tracing the Roots of Terrorism

Beginning in the late 1800s and continuing through the years following World War I, western diplomats partitioned many areas across the world, ignoring the geographic and cultural complexity of these places. Friedrich Nietzsche's quote, All things are subject to interpretation”whichever interpretation prevails at a given time is a function of power and not truth, seems to appropriately characterize this process.

Certainly geographic truth and logic weren't used in delineating those political boundaries. The goal of partitioning the land and national boundary delineation was the distribution of control to various European nations and their complicit local regimes.

Political boundaries were redrawn across Eastern Europe, southwest Asia, Africa and the Middle East, largely by western European men with minimal understanding of the human geography of these regions. These decisions laid the foundation for many of the tribal and ethnic conflicts leading to the insurgencies and terrorist groups of the 21st century.

Western diplomats, soldiers and citizens continue to ignore many of the core beliefs, economic disparities, aspirational geographies and on-the-ground realities of the people, clans, tribes and cultures of these areas. It's imperative to recognize and comprehend the philosophies, cultural organization and physical landscape realities that compose the fabric of terrorist groups from a geographical perspective.

The focus for an aspirational homeland and cultural place for many terrorist groups, whether they are nationalistic, cultural or ideological, is a geographic area to control as their own. One such example is the geographic territory Osama bin Laden and the leadership of al Qaeda declared as the nucleus of a global caliphate comprising The Levant, Iraq, Palestine, the Arabian Peninsula and Egypt.

Another example is the aspirational Kurdistan-encompassing areas of Turkey, Syria, Iraq and Iran. These cultural imperatives of various groups and their support communities have geographic manifestation in aspirational homelands, insurgent state creation and the quest for safe havens, all of which are crucial to understanding and countering future terrorists.

The spatiality of terrorist activities within multiple domains is of utmost importance. Twenty-first century terrorists operate in several domain spaces”geographic space, which bounds everything physical or geographic; social space, which bounds all social interaction; and virtual space, i.e., the space created by the Internet and the World Wide Web via the information age.

Terrorists live, interact and attack in geographic space, while the communicative interactions that facilitate terrorist networks take place in layered social and virtual spaces. While use of the Internet and social networks are foci of counterterrorism, social and virtual spaces require people and infrastructure in geographic space.

Geographic Context Creates Critical Insights

Although it isn't widely held that geography determines human behavior, the influence of physical and human geography on terrorist motivations, behavior, options and activities are primary considerations in understanding terrorism.

Terrorism is a complex phenomenon and is best studied through a multidisciplinary approach. Geography acts as a science of convergence, where many disciplines intersect in the study of phenomena and processes within a geographic context.

Geographic truth and logic haven't been used to delineate the world's political boundaries, laying the foundation for many of the 21st century's tribal and ethnic conflicts, insurgencies and terrorist groups.

Geographically referenced data (geospatial data) of these physical and human phenomena are interpreted to create geospatial information for investigating spatial patterns from which an underlying process can be inferred, analyzed and explained within a map and geographic information system (GIS). Such information can create knowledge, conveyed as integrated maps, images, spatial-temporal models of change and predictive assessments.

This approach forms the basis for more informed policy and practices, forming the core of GEOINT and the broader geographic perspective. Understanding terrorism in a more complete, explicitly geographic fashion, using geographic concepts linked to the most current geospatial analytical tools, is essential to pre-empting and countering terrorism in the future.

Publisher’s Note: Hepner and Medina are collaborating on The Geography of International Terrorism, which will be published in spring 2013 by Taylor and Francis, CRC Press.

Educating at the Speed of GEOINT

Specialized knowledge is critical for today’s GEOINT professionals to understand and exploit the world’s rapidly expanding volume of geospatial data.

By Lt. Col. Michael L. Thomas, Ph.D., professor, Department of Geography, The Pennsylvania State University (www.geog.psu.edu), University Park, Pa.

Many inside and outside the government recognize that events such as the Arab Spring can be planned and achieved faster than ever using Facebook and Twitter and then broadcast to the world via YouTube. When adding the geospatial dimension, regional differences in social moods or social interests become observable and can be described as geospatial intelligence (GEOINT) signatures of human behavior. When organizing cyber data around space and time, both static and transactional events emerge as patterns of life when aggregated and integrated with traditional GEOINT tools and methods.

This new and rich source of data and data integration requires a GEOINT professional prepared to understand and communicate the relevance of the seemingly nonspatial cyber information embedded in hundreds of thousands of communiqués. To meet this challenge, social media, robotic data collection technologies, analytic techniques, remote sensing, and geographic information system (GIS) methods are being integrated and incorporated into the educational curriculum of Penn State's GEOINT program.

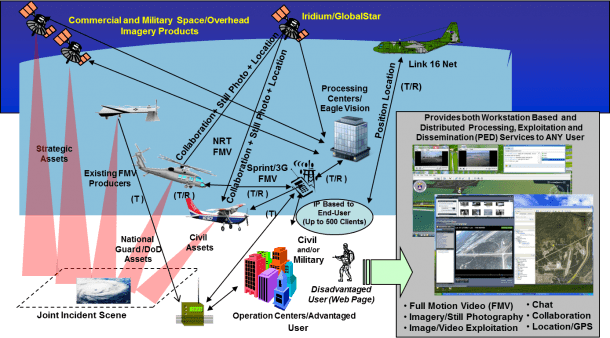

Before the start of the Global War on Terror (GWOT) in 2001, GEOINT processes and tools were mostly directed at traditional Cold War threats with structured data sources, well-defined functions and distinct activities. Today, the GEOINT environment is fluid with a mix of information increasing in volume, variety and velocity, as shown in the figure below. An example of the explosion in the volume of data is DigitalGlobe's constellation of imaging satellites, which collects millions of square miles of high-resolution imagery daily.

An overview of a geoinformation tasking/collection/exploitation architecture comprises federal, state and private resources. The end user might be an operations/fusion center or even a disadvantaged user with only a browser on some type of portable device.

Added to this volume and variety of previously unavailable remote sensing imagery is full-motion video (FMV) and social media, which further help to reveal the signatures of human behavior. Taken as a whole, these technologies provide both decision advantages with insights and enhance decision confidence unavailable through other techniques. All this makes collaboration both possible and essential on more levels than ever before. It's imperative that the GEOINT and educational community look toward integration.

Few things happen in isolation”an event response usually requires a coordinated understanding of the situation and action from multiple organizations. GEOINT is essential to understanding the scope and nature of an event prior to taking action. Government in the past provided this GEOINT because of their information sources, but times are changing. GEOINT data sources used for planning a response need not originate from a government agency.

The existence of increasing capable commercial and open data sources provides a viable alternative to government systems. This is to say, commercial and crowd-source data can be incorporated into a meaningful big picture about an incident. Here current intelligence, derived from open sources and superimposed on satellite imagery or aerial photography, provides a near real-time context for effective coordinated action.

Many think CYBER combined with GEOINT solely involves mapping the Internet or defending networks. Rather, it's all about the flow of information, the effects of the connective technologies, and the redefinition of geographic terms like distance and neighborhood. CYBER activities can be transformed and referenced in terms of Euclidean space and time to create actionable intelligence.

Emerging GEOINT skills require specialized training and education for the analyst to integrate foundational imagery from a variety of standards and nonstandard sources such as a commercial satellite, a private unmanned aircraft system, a news helicopter or even a cellphone. A common architecture that also can ingest, process and display such imagery must be designed, planned and used by personnel who understand what such combined sources bring to the response table.

Providing a contextually rich situational display on devices such as smartphones and tablets is the expectation. These devices can be expected to chat both in text and images among responders in a free-flowing fashion. The flow of useful GEOINT information is limited only by the responder's imagination, which is only limited by education to the possibilities.

Collaboration, knowledge sharing and effective communications are more necessary than ever. This has created a demand for education in GEOINT. The ability to use spatial thinking and models to develop actionable GEOINT is a critical skill when working in a multidisciplinary and multiagency team.

Publisher’s Note: Thomas is assigned to the Naval Space and Warfare Center, Charleston, S.C., as a systems engineer in the Communications and Networks division. He currently is stationed at Patch Barracks, Stuttgart, Germany, as a knowledge management engineer in the Cyber Division.