Despite a downward trend in government spending on space, Earth observation programs continue to expand globally.

By Adam Keith, director of Space and Earth Observation, Euroconsult (www.euroconsult-ec.com), Montreal, Canada.

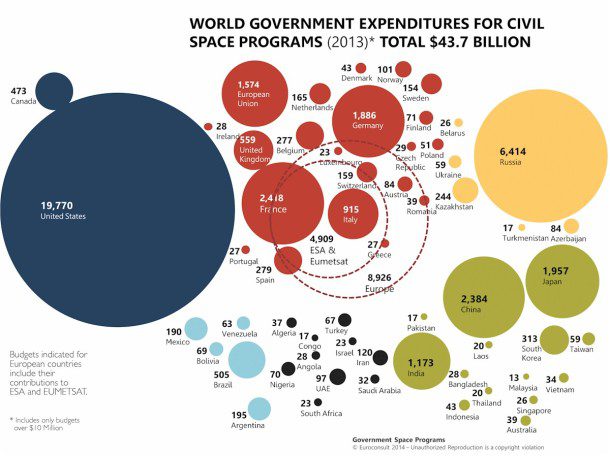

Last year marked the first year of decreased government spending on space programs since 1995. After years of continuous growth, global budgets for space programs have flattened at around $70 billion since 2009. Following the last peak at $73 billion in 2012, global government spending for space decreased to $72.1 billion in 2013”$43.7 billion aligned to civil programs and the remainder to defense, according to recent Euroconsult research.

However, overall government investment in Earth observation (EO), particularly civil investments, somewhat bucks the decreasing space budget trend. In 2013, the global civil EO budget totalled $8.6 billion, a 12 percent increase since 2012. Although historical investors in the sector (United States, European Union, Japan, France, etc.) are expected to remain the largest individual EO budgets, fast-developing and emerging programs around the world are expected to drive growth.

Why the Slowdown?

Governments pursue diversified objectives when investing in space. Their mandate to support industry research and development and scientific research requires stable, long-term funding to achieve overarching goals. Public investment in space is also intrinsically cyclical, because ultimately it is driven by the public sector's requirements for infrastructure deployment for satellite and other orbital assets. This is one of the reasons why there's a slowdown in government space spending after so many years of expansion.

The reduction's magnitude and its effect on government procurement practices couldn't be foreseen. Public investment to support the world economy increased government debt levels, creating unparalleled tensions and uncertainties about public finances that have constrained most governments to prioritize state spending. The situation has pushed governments toward severe budget arbitrations, prompting tough choices about spending priorities.

Space is no exception. The eurozone debt crisis and the U.S. budget sequestration are two prominent examples of how budget uncertainties have affected the world's two leading space programs. However, the current worldwide context for public space programs also shows many positive signs prompted by the emergence of regional leaders and an ever-growing number of nations that have started or plan to build space-based capabilities.

Changing the Status Quo

The number of countries investing in space around the world keeps increasing year after year. In 2013, 58 countries invested $10 million or more in space applications and technologies, compared with 37 in 2003. In addition, 22 more countries have plans to invest in space projects. Such dynamism demonstrates how governments see space technologies and applications as valuable investments to support their national social, economic, strategic and technological development.

The United States invested $39.7 billion in its space program (civil and defense) in 2013. This is an $8.8 billion reduction compared with the peak spending of $47.5 billion in 2009, mainly brought about by a reduction in defense spending, and a key factor for the overall global space budget investment decrease.

On the other hand, Russia recorded a massive increase of its public investment in space and is the only country besides the United States to pass the $10 billion cap. In the last five years, Russia's investments have accelerated at an impressive average growth of 32 percent in local currency.

Another six countries and the European Union invested more than $1 billion: Japan, China, France, Germany, Italy and India. China's eighth-place ranking for space spending as a ratio of its gross domestic product indicates there's room for future investment growth.

Another 19 countries recorded more than $100 million in spending. However, the major difference is in the 30 other countries that invested between $10 million and $100 million in their national space programs; only 10 of them were part of that list in 2003. Emerging countries are establishing themselves as a key market driver for the space industry.

EO Expansion

Within these emerging programs, EO represents the first area of investment. Countries with rapidly expanding EO programs, such as India, Russia, China and South Korea, expect to gain autonomy through operational missions that support growing domestic demand for applications such as resources management, mapping, etc.

Although these programs are diverse, they exhibit common traits, including a focus on continuing and enhancing flagship programs, launching nationally built optical and radar satellites, commercializing data sales and increasing international cooperation. The latter element is particularly evident as these programs expand into science-specific missions, often in cooperation with leading space agencies such as NASA and the European Space Agency (ESA). Thus, countries such as India and China have started to play a greater role in collecting data to support environmental monitoring objectives.

Although these programs are diverse, they exhibit common traits, including a focus on continuing and enhancing flagship programs, launching nationally built optical and radar satellites, commercializing data sales and increasing international cooperation. The latter element is particularly evident as these programs expand into science-specific missions, often in cooperation with leading space agencies such as NASA and the European Space Agency (ESA). Thus, countries such as India and China have started to play a greater role in collecting data to support environmental monitoring objectives.

For emerging space nations, EO represents the primary area of investment compared with other space-sector applications, as it represents affordable access to space capabilities. Such programs often are developed within the wider framework of a technology-transfer program with an established industry or agency partner to assist in developing domestic industrial capabilities and supporting further program advancement. In total, more than 40 countries are anticipated to launch an EO satellite by 2023, compared with the 58 countries investing in space applications.

Driving EO Investment

Several factors drive countries to develop EO capabilities when initiating their space program. The first is to develop skilled workers, leading to an autonomous high-tech manufacturing capability and potentially a space program. For instance, the development of national industry has been a primary focus of EO programs in Algeria, Nigeria and Malaysia.

Lower cost of entry when compared with other satellite applications also makes the sector attractive. As an initial first step, numerous countries start the EO program with a technology demonstrator mission; the purpose is first to test technology and then to gain public and industrial interest in EO capabilities.

Following initial missions, developing nations such as Thailand, Malaysia and Algeria seek to develop next-generation satellites with operational data supplies, meaning the data are collected with users in mind who have returning requirements for services. After first- or second-generation launches, these emerging space nations need to decide on a stable, longer-term investment. Funding is required to support EO program development, including replacing and launching new satellite missions.

As cyclical budgets needed to finance specific satellite missions in emerging EO programs convert to stable budgets to support wider development, overall investment in the EO sector increases. In addition, more countries will be added to the mix. For example, Mexico, Azerbaijan and Peru, among others, are expected to launch EO capacity within this decade. Kazakhstan recently entered the fray with the launch of its first EO satellite on April 29, 2014.

Such countries will continue to boost overall investment into the EO sector and increase overall data supply. With this in mind, although historical NASA and ESA EO programs face budgetary issues, the overall investment in EO is expected to remain high in the short to medium term as more programs become established and build on initial forays into EO satellite development.